Dying Leather Blue

Additional information on both assumptions that I have made and processes in rendering materials for the dye process are available separately within the Assumptions and Terminology and Rendering Dye Materials pages.

Source material and interpretation of methodologies

The Secretes of the Reverende Maister Alexis of Piemount1 contains a formula for dying leather a very blue color using an elderberry mixture.

Though an alternate translation2 is available, my attempt at a direct translation would be as follows:

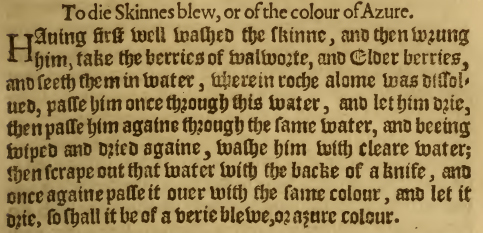

"To die Skinnes blew, or the color of Azure.

Having first well washed the skinne, and than wrung him, take the berries of walworte, and Elderberries, and seeth them in water, wherin Roche Alome was dissolved, passe him once through this water, and let him drie, than passe him againe thorowe the same water, and beeing wiped and dried againe, washe him with cleare water; then scrape out that water with the back of a knife, and once again passe it over with the same colour, and let it drie so shall it be of a verie blewe, or azure colour."

From the source material, I'm reading the instructions on the dye process for this as follows:

1) Begin by cleaning the skin thoroughly, then wring it out.

This statement in the process would lead me to believe that the dying itself was included

as a part of the tanning process. In the current manner of purchasing a vegetable tanned leather that's already been tanned, the skin should not need to be cleaned again - since the fat and residual flesh bits are already scraped off for us.

This being the case though, it is of note that the soaking and wringing out of the skin should still be utilized so that the moisture in the skin will more readily accept any color that it is exposed to (as opposed to using the dye on a dry piece of leather). This is generally the case for modern stains and dyes that are water based as well. Damp leather allows water based commercially available products to soak in more as it blends into the present moisture.

2) Prepare the dye solution

In this case, the Maister references preparing water by dissolving alum in it prior to boiling the elderberries in it. This part of the process should serve two purposes. When alum is added to a dye, it acts as a mordant3, allowing the dye itself to set better by fixing itself to the fibers of the leather. At the same time, it may intensify or darken the color of the dye itself. In this application, I think that it was being prepared as such to darken the color of the elderberries enough to achieve the very blue color that he spoke of.

3) Let the dye vat cool

The Maister did not include this step, so why am I putting it in here instead of following his instruction alone? If you've ever put a piece of leather into boiling water (dyed or not), you know that this leads into hardening of the leather. This is an experiment on dye processes, I will attempt cuir boulli separately. Hot water will compress the fibers of the leather more than I'm attempting to produce here, but it is of note that the dye itself will work its way into the fibers of the leather if it is warm - not cold. I am looking for a balance point in this process in which I could place my hand into the dye vat and the contents be close to body temperature.

4) Imerse the side in the dye solution

In this translation, the Maister instructs to pass the skin through the dye vat three times with slight variance in each pass. After the first pass through the dye vat we are told to wipe it down and let it dry. This should give us a good base for the color and, after it dries from the first pass, a basis for comparison on additional passes. After the second pass through the dye we are told to rinse the skin with clean water, then scrape the water out of the skin with the back of a knife. The rinsing with clean water after the second immersion should also help to push the dye into the fibers of the skin at the same time as washing the excess off of the surface

where it may have dried up in the first pass. The third pass simply states that you should pass the skin through

the dye vat once more and let it dry completely. This should render the surface completely colored, where the

first two passes seem to be making certain that the dye is worked all the way through.

Constructive feedback is both welcome and appreciated, please let me know if I missed some pertinent information or if there's somewhere I can improve.

As always, thanks for reading!

Ihone

- The secrets of the reverend Maister Alexis of Piemont by Girolamo Ruscelli. OL25228326M

Translated from French into English by William Ward - Screen shot is of page 179 of the viewable pdf on Open Library

- Medieval Leather Dying by Marc Carlson, original compilation by Ron Charlotte also has a direct translation available.

- Wikipedia, entry about what a mordant is, along with entries on usage